WQPT PBS Presents

Hampton Snapshot

Special | 9m 30sVideo has Closed Captions

Hampton Snapshot

The story of river town Hampton, Illinois. It's founding and the infamous riot that took place on the steamboat Dubuque.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

WQPT PBS Presents is a local public television program presented by WQPT PBS

WQPT PBS Presents

Hampton Snapshot

Special | 9m 30sVideo has Closed Captions

The story of river town Hampton, Illinois. It's founding and the infamous riot that took place on the steamboat Dubuque.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch WQPT PBS Presents

WQPT PBS Presents is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Short 'snapshot' stories from around the Quad Cities area.

Providing Support for PBS.org

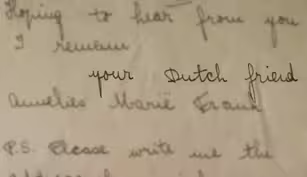

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(upbeat music) (serene piano music) - [Narrator] The village of Hampton, Illinois was originally in territory claimed by the Sac and Fox Indians.

Originally known as McNeil's Landing, it was platted as Hampton in 1838.

A small portion north of present-day 7th Street was platted as Milan.

And since there already was a Milan, this portion was incorporated into Hampton.

The paper town did not sell initially because of the swampy riverfront and being adjacent to the north end of the Rock Island Rapids.

However, settlers drained the swamps by the end of the 19th century and the village was founded in 1900 as Hampton.

At one time, Hampton vied with Rock Island to be the county seat.

- There was a rivalry between Hampton and Rock Island for the county seat.

There will be a variety of reasons involved.

Saranus Brettun, who helped lay out the town and had the Brettun & Black store, had a reputation for being a very difficult person to get along with.

So some people blamed him that people didn't want to bring the county seat here.

It might be more that Rock Island had more room to grow.

The bluffs here in Hampton are so close to the river that there really wasn't very much space to grow.

Rock island had a lot more.

That might've been a factor.

You had Ford Armstrong down there, so you had people of influence who were already living in the area.

So those were the more likely reasons why Rock Island got to be the county seat.

- [Narrator] Hampton was a prime location for clammers to camp and harvest millions of native mussels to make buttons and perhaps in hope of finding Mississippi pearls.

(dramatic piano music) And though it may have lost the county seat to Rock Island, Hampton retains many of the original buildings associated with the villages downtown, which included saloons, a barber, churches, a blacksmith shop, and the mercantile.

- It's called the Brettun & Black Museum because it was built as a store for two men, Saranus Brettun and Francis Black, and it was built in 1849.

And it was a type of store which we would call a mercantile store.

In other words, there wasn't a lot of cash that changed hands.

It was mostly bartering.

Farmers would bring in hogs that they had raised and they'd butchered.

They'd bring them in in the fall.

And then, those hogs were cut up.

They were packed in barrels and salted, 'cause there wasn't refrigeration at that time.

And then, they would trade for the goods that were here in the store, things that they couldn't grow for themselves or things that they needed, like fabric, or molasses, or you could even buy a John Deere plow here in 1849.

The steamboats at that time were both for trading and for passenger travel.

They would dock here.

Generally, they were bringing in goods or supplies that were needed.

I mentioned that they packed pork here.

They went through as much as 20 tons of salt in a year because there was no refrigeration, and so that's how they did it.

But there'd also be passengers who were coming here to Hampton.

Hampton was a major trading area at that time.

People would come from as far away as the area, which is now Geneseo, but they'd also know from Iowa.

Any of the local residents who know Wells Ferry Road on the Iowa side, it has that name because it came all down to the river and there was a ferry operated by a man named Lucius Wells here at Hampton.

So the Iowa farmers would come here as well as Illinois farmers.

There were a whole variety of businesses, saloons, obviously.

But there was a milliner making dresses and there was a barber.

And because they packed so much pork, there were eight Cooper shops.

Cooper's made barrels.

There were blacksmiths.

There was a druggist.

There was a pharmacist.

So the whole variety that you would have in a major trading center.

Don't think of Hampton's ever having been a major anything, but it was then when towns were much smaller, and it was a hub.

(peaceful piano music) Saranus Brettun was in here until about 1857, 1858, right along in there, and then he moved to Iowa.

And that's when Francis Black took over, and then he was in partnership at various times.

There's a man named Milton Crapster, who was his son-in-law.

They were in partnership for a while.

Eventually, he became a partner with his own son, Walter Black.

So Francis Black stayed in this business until the early 1900s, more than a 50 years.

He was in business here.

At the end, he was in business with his son.

His son kept the store after Mr. Black retired.

Eventually, the store came into the hands of a man named Charlie Sikes, who had it in the '20s and '30s as his own private museum.

And this is a very unique building in that it's extremely well-documented.

Mr. Black kept all of his business records and they stayed in this building.

Mr. Sikes was an amateur historian.

He kept the records as well.

And those records, when Mr. Sikes passed away, were part of an auction.

They went to the Davenport Public Museum, which we now know is the Putnam museum, and they're all still over there.

So this is an incredibly well-documented building.

We can tell you the kinds of things they sold and how many bricks it took to build a building, and a whole variety of things because of those records.

I mentioned all those tons of salt that were used.

They came in on the steamboats.

And they came in through the basement level, but they couldn't stay there because the humidity would spoil the salt.

Of course, the goods were all being sold up here so they couldn't get the salt to be on the first floor.

They had to go all the way to the second floor.

So tons of salt were hauled up and down there, as well as other goods that they sold that weren't on display, like the John Deere plows I mentioned.

- [Narrator] One of the most infamous episodes in Hampton history was the race riot at Hagy's Landing on July 24th, 1869, aboard the Steamboat Dubuque.

- Steamboat Dubuque, which was coming into dock at Hampton, not here at Black store, but another store down the block, Hagy's store.

There were three stores in Hampton that had steamboat docks.

There were lumber raftsmen.

Now, lumber raftsmen where the people who helped bring logs down to the quad city.

(indistinct) wasn't quad cities then, but Davenport, Moline, Buffalo all had big sawmills.

So the logs were cut in Wisconsin, floated downriver, made into rafts.

And when they got to the Mississippi River, the smaller rafts that had come down the Wisconsin River, were made into great, big rafts, bigger than a football field sometimes And it took these raftsmen to help guide it and work on it and that sort of thing.

But it was hard work.

They were kind of roughneck-type people.

And so they got as far as Davenport, and then they had to go back up to Wisconsin where they had originated, and there was a dispute right here around Hampton.

It's a little confusing, the details, but I believe they put in, at Hagy's store, they picked up some passengers.

And then, the deckhands on the steamboat were mostly African-American.

One of the deckhands was assigned to stand by an area that went to the cabins.

Cabin passengers paid more than what were called deck passengers.

So they had to check the tickets, and they didn't want any of the deck passengers sneaking up and not paying.

So they had this African-American guy, Moses Davison, standing there.

And a man named Lynch, who was one of the raftsmen, came there and wanted to go up the stairs.

And Mr. Davison said he couldn't.

And then, there ensued an argument, and then a fight.

And then, pretty soon the fight turned into a riot.

The riot was such that the raftsmen, who were an unruly group on all boats going back north, started chasing around the African-Americans, throwing them off the boats, stoning them with big pieces of coal, stabbing them with knives.

Five African-American men lost their lives in the riot.

There were a lot of raftsmen.

They were mostly Irishmen, according to their surnames anyway.

There were a lot of ethnic hatreds in those days, but this was specifically racial.

There's no question about that.

They didn't chase the white deckhands around, just the African-American deckhands.

And so, eventually, the rioters forced the steamboat to keep on going upriver.

They wanted to get away.

They got as far as Clinton, but the Rock Island county sheriff had sent a posse on a train all the way to Clinton, and they captured them in there.

They turned the boat around, brought it back to Rock Island.

They tried to identify those raftsmen who were rioters, those who weren't.

Finally, 10 men stood trial.

And then, they changed the venue from Rock Island to Henry County.

So the trial took place in Cambridge.

For nine of the men, seven were found guilty.

Two were found innocent.

They were given prison sentences for manslaughter that ranged from three years to one year.

The leader of the writers, a man named Lynch, who started the whole thing with Mr. Davison.

He had his trial separately in Rock Island.

He was found guilty and he was given 10 years for manslaughter at the state prison in Joliet.

- [Narrator] In 1876, the ill-fated ship burned at Alton Slough while in Winter Quarters.

Today, the Brettun & Black mercantile is a museum and is available for you to tour.

(peaceful piano music)

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

Support for PBS provided by:

WQPT PBS Presents is a local public television program presented by WQPT PBS